Highlight

Native Hawaiian birds and the evolution of resistance to an introduced disease

Achievement/Results

The Hawaiian Islands and other islands of the Pacific have already seen severe losses of biodiversity due to a variety of factors, including habitat loss, climate change, introduced predators and competitors, and introduced diseases. An endemic subfamily of birds, the Hawaiian honeycreepers, are considered worldwide as a remarkable example of adaptive radiation.

Yet most species of Hawaiian honeycreepers are endangered or already extinct. Introduced diseases, including avian malaria, are considered the greatest threat to the persistence and recovery of Hawaiian forest birds. Therefore it is critical to understand how surviving species are coping with disease, and apply this knowledge to closely related groups on the brink of extinction.

Most Hawaiian forest birds survive in the high elevation forests on the islands of Maui and Hawaii, where temperatures are too cold for the mosquito that transmits the malaria parasite. However, Oahu lies at an elevation where the temperature is suitable for mosquitoes year round, acting as a model for what disease transmission may look like as warming temperatures decrease the amount of ?safe? habitat at high elevation forests.

For her dissertation research, IGERT Fellow Kira Krend conducted a study of avian malaria on Oahu. Most native forest birds on Oahu have gone extinct, yet Oahu amakihi, a small, green Hawaiian honeycreeper, is not only surviving but maintains a stable and widespread population.

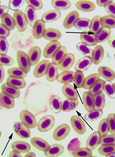

Her study included a groundbreaking project on avian malaria in experimentally infected Oahu amakihi. All infected birds mounted an immune response and survived infection; peak parasitemia was the lowest documented of all Hawaiian forest bird species ever examined. Future work determining the mechanisms that allows Oahu amakihi to resist infection may hold the key to the survival of Hawaiian honeycreepers.

IGERT affiliated faculty Professors Lenny Freed and Rebecca Cann collaborated on this study, along with Professor Diane Wallace Taylor and her human malaria lab in the Department of Tropical Medicine, also at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Dr. Taylor’s lab uses a cutting edge Luminex microsphere multiplex assay to detect malaria antibodies placenta and cord blood of mothers and babies from malaria endemic regions. Applications of this technology to wildlife disease is rarely done; this collaboration represents the first time this assay has been used for non-human malaria or any avian disease. IGERT Trainees Sam Bader, Jon Winchester and Randi Rhodes also collaborated on this project.

The research is vital to the protection of US endangered species, 25% of which occur in Hawaii. Such research addressing critical questions combined with cutting edge technology are vital to preserving biodiversity. The research also represents a unique collaboration between the Honolulu Zoo and the University of Hawaii, strengthening the connection between both entities for future collaboration. Oahu amakihi from this experiment are now part of the Honolulu Zoo’s collection, and will be used for both public display for education, as well as become the beginning of a captive breeding program.

In addition, many UH undergraduates also assisted with this project, giving students a chance to interact with native Hawaiian birds as well as exposing them to science. One undergraduate Honors student collaborated on this project for her thesis, giving her a unique opportunity to conduct behavioral observations of a species that is not held in captivity anywhere else in the world.

Address Goals

This project provided a unique integrative research opportunity. It combined the knowledge of leading researchers in human malariology and zoology, along with cutting edge research technologies, and methods from entirely different fields. Not only has this yielded new insights into the affects of introduced malaria as a potential contributor to the endangered birds species in Hawaii, it opens up a new avenue for human malaria research. This unique collaboration potentially may yield new understanding of human malaria and control methods, such as vaccines, for addressing what is second only to HIV as the world’s most challenging infectious disease problem.

The project involved the collaboration of a large group of researchers, graduate students and undergraduates, exposing all of them to new ideas, ways of thinking about and approaching malaria research, while developing new research skills. Moreover, because a key portion of the research involved the Honolulu Zoo, the research and information, such as the life cycle of the malaria parasite will be incorporated into the display and interpretation materials. As tens of thousands of people visit the facility annually, the potential impact on scientific literacy is significant.